Xen and the Art of Virtualization

Xen and the Art of Virtualization

-

Paul Barham

-

Boris Dragovic

-

Keir Fraser

-

Steven Hand

-

Tim Harris

-

Alex Ho

-

Rolf Neugebauer

-

Ian Pratt

-

Andrew Warfield

Paper Overview

-

A big idea paper. (Why read any other kind?)

-

Also a wrong way paper.

-

Full virtualization.

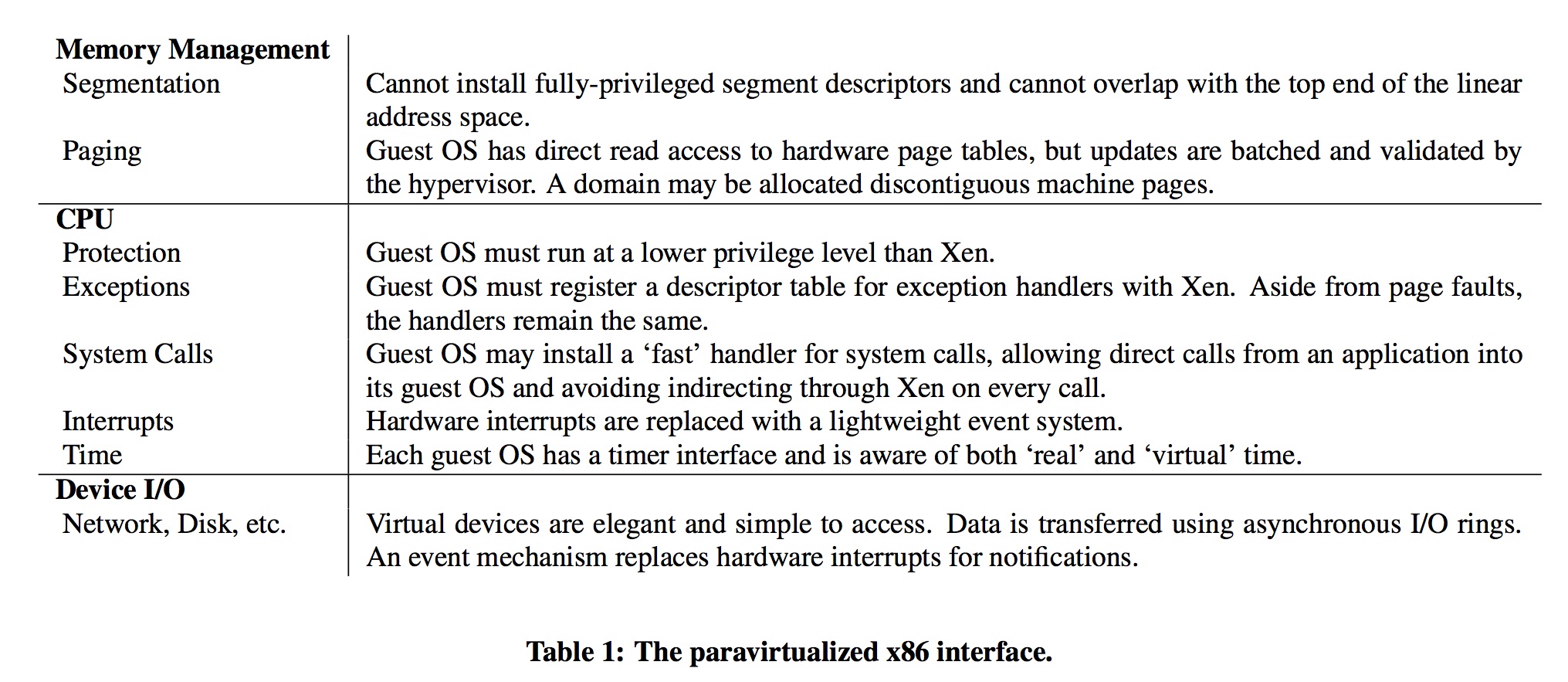

Support for full virtualization was never part of the x86 architectural design. Certain supervisor instructions must be handled by the VMM for correct virtualization, but executing these with insufficient privilege fails silently rather than causing a convenient trap. Efficiently virtualizing the x86 MMU is also difficult. These problems can be solved, but only at the cost of increased complexity and reduced performance.

Notwithstanding the intricacies of the x86, there are other arguments against full virtualization. In particular, there are situations in which it is desirable for the hosted operating systems to see real as well as virtual resources: providing both real and virtual time allows a guest OS to better support time-sensitive tasks, and to correctly handle TCP timeouts and RTT estimates, while exposing real machine addresses allows a guest OS to improve performance by using superpages or page coloring.

-

Paravirtualization. Trade off small changes to the guest OS for big improvements in performance and VMM simplicity.

Xen Design Principles

-

"Support for unmodified application binaries is essential, or users will not transition to Xen. Hence we must virtualize all architectural features required by existing standard ABIs."

-

"Supporting full multi-application operating systems is important, as this allows complex server configurations to be virtualized within a single guest OS instance."

-

"Paravirtualization is necessary to obtain high performance and strong resource isolation on uncooperative machine architectures such as x86."

-

"Even on cooperative machine architectures, completely hiding the effects of resource virtualization from guest OSes risks both correctness and performance."

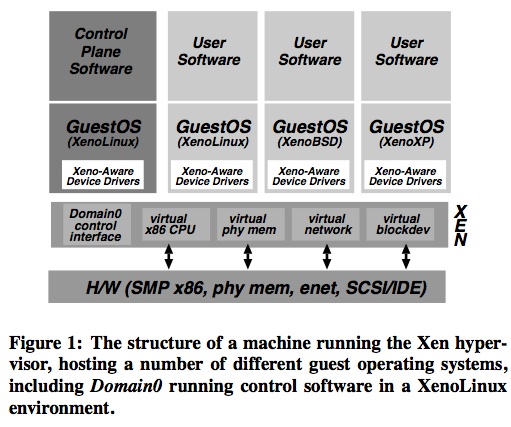

Xen introduces the idea of a hypervisor, a small piece of control software similar to the VMM running below all the operating systems running on the machine. Much of the typical VMM functionality is moved to control plane software that runs inside a Xen guest.

Virtual Machine Memory Interface

Virtualizing memory is hard, but it’s easier if the architecture has

-

a software-managed TLB, which can be efficiently virtualized; or

-

a TLB with address space identifiers, which does not need to be flushed on every transition.

Given these limitations, we made two decisions: (i) guest OSes are responsible for allocating and managing the hardware page tables, with minimal involvement from Xen to ensure safety and isolation; and (ii) Xen exists in a 64MB section at the top of every address space, thus avoiding a TLB flush when entering and leaving the hypervisor

But how then do we ensure safety?

Each time a guest OS requires a new page table, perhaps because a new process is being created, it allocates and initializes a page from its own memory reservation and registers it with Xen. At this point the OS must relinquish direct write privileges to the page-table memory: all subsequent updates must be validated by Xen.

Guest OSes may batch update requests to amortize the overhead of entering the hypervisor. The top 64MB region of each address space, which is reserved for Xen, is not accessible or remappable by guest OSes. This address region is not used by any of the common x86 ABIs however, so this restriction does not break application compatibility.

Virtual Machine CPU Interface

Principally, the insertion of a hypervisor below the operating system violates the usual assumption that the OS is the most privileged entity in the system. In order to protect the hypervisor from OS misbehavior (and domains from one another) guest OSes must be modified to run at a lower privilege level.

x86 privilege rings to the rescue!

Efficient virtualization of privilege levels is possible on x86 because it supports four distinct privilege levels in hardware. The x86 privilege levels are generally described as rings, and are numbered from zero (most privileged) to three (least privileged). OS code typically executes in ring 0 because no other ring can execute privileged instructions, while ring 3 is generally used for application code. To our knowledge, rings 1 and 2 have not been used by any well-known x86 OS since OS/2.

What exceptions happen enough to create a performance problem?